The Summer of Challs: Week 2

Back from vacation, so time for more CTFs. The only one I could really find this week was TJCTF, and I did the first 5 web challenges. I’m not sure that these were the most interesting/challenging, but I’m looking for quantity over quality.

FROG

I’m only really putting this one in here for completion. You open the website to see some text that says ribbit ribbit ribbit :( robbit robbit robbit :(

The source code for the html page had nothing but HTML text. From here, I got the idea to check robots.txt, which is a file in a web app that tells search engine crawlers which URLs they can and can’t crawl. Upon accessing it, I found this:

User-agent: *

Disallow: /secret-frogger-78570618/

I went to this endpoint, and saw this:

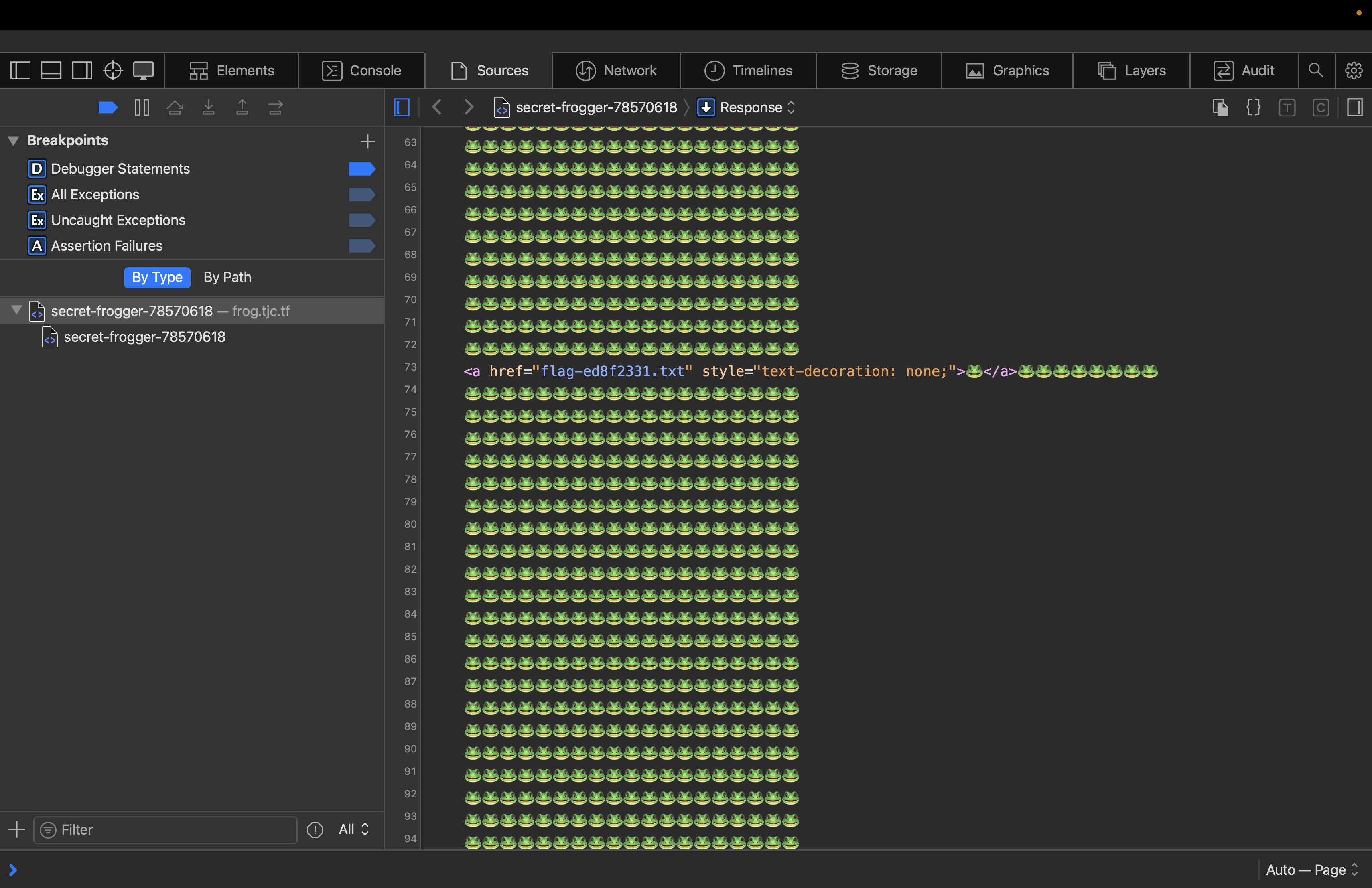

I viewed the source code for this, and saw something interesting:

Clicking on the link, we get the flag.

SITE READER

This is a simple web app that shows some text and a box to enter a “site to view”. We can type a link in, and submit it.

When we submit a link like google.com, the server the app is running on goes to the link and renders it on the web app:

At this point, I’m thinking this is something related to Server Side Request Forgery (SSRF), where we can get the server to access resources inside itself or external to it on our behalf, through some abuse of parameters. In this case, submitting a URL that is not exactly benign.

I checked the source code for the app, which was made with flask. There is a flag.txt file in the server that is opened, parsed into a flag variable, and printed when we visit the monitor endpoint of the website:

def monitor():

if request.remote_addr in ("localhost", "127.0.0.1"):

return render_template("admin.html", message=flag, errors="".join(log) or "No recent errors")

else:

return render_template("admin.html", message="Unauthorized access", errors="")

However, this only displays the flag, as the code shows, when the endpoint is reached from localhost. In other words, unless the server itself is visiting the /monitor endpoint, it won’t show the flag, and will instead show “Unauthorized access”.

From here, we can craft a url that the server will fetch, and in fetching it, will actually make a request through the loopback interface (localhost) to the monitor endpoint. Another thing to note before doing this is that since it is a flask app, it is probably running on port 5000.

I entered this: http://localhost:5000/monitor, and got the flag:

The difference between entering http://site/monitor and http//localhost:5000/monitor is that the former will cause the server to access the monitor endpoint through the public IP address, and therefore through the internet, like any normal user. The latter, on the other hand, tells the server to access the monitor endpoint within its internal network, through localhost. Usually, SSRF challenges would have some kind of sanitization in what we input, but this one seems to be simpler.

FETCHER

We are presented with another simple webpage, with another box to enter a URL. The page says it will “fetch the URL from our address”. This one is a bit stranger, if I enter a URL, nothing is rendered. I’m not sure if the web app itself was just buggy, or the server was only fetching the URL and not rendering it on the webpage, so the next step was to check the provided source code.

The app.js file checks if the beginning of the string we enter starts with http:// or https://. If it doesn’t start with that, it returns the string invalid URL. It also checks (and doesn’t allow) a request including the word localhost or the numbers 127.0.0.1 in the url. This is basic protection against SSRF, something the last challenge lacked.

There is also a flag endpoint with some interesting code:

app.get('/flag', (req, res) => {

if (req.ip !== '::ffff:127.0.0.1' && req.ip !== '::1' && req.ip !== '127.0.0.1')

return res.send('bad ip');

res.send(`hey myself! here's your flag: ${flag}`);

});

If we make a request to the /flag endpoint normally, it will check if we are doing it server side or client side. If we do it client side, it just shows the text “bad ip”. However, we can’t simply make a request with localhost in the url like in the last challenge, because the app is now sanitizing our URLs. My first thought was to make our own webserver with a normal URL that would return the HTTP redirect code to localhost/flag. When the server would make a request to our server, it would bounce back, check the flag endpoint through localhost, and bypass the check. However, this wasn’t working for some reason.

I then noticed that the filter doesn’t check for IPv6 addresses, and got the idea to submit the IPv6 version of localhost. I found how to put this in URL form in this article, Stack Overflow IPv6, and submitted this:

http://[::1]:3000/flag

We then can see the flag:

Looks like its not so easy to sanitize URL inputs - there’s a lot of possible workarounds.

TEMPLATER

This one at first appeared to be very strange:

It took a bit of playing around, but I eventually realized you can submit a key and value pair to make a new “template variable”. We can then put the key in the Use Template Variables box in the form of {{key}} (this is for the Jinja2 template engine), and we would be taken to another page that rendered the value.

Whenever we write a template in the Use Template Variables, we make a POST request to the /template endpoint of the app, and we can then see it rendered.

When I looked at the source code, I found this:

flag = open('flag.txt').read().strip()

template_keys = {

'flag': flag,

'title': 'my website',

'content': 'Hello, {{name}}! ',

'name': 'player'

}

Just POSTing the data {{flag}} won’t work, because of this code:

app.route('/template', methods=['POST'])

def template_route():

s = request.form['template']

s = template(s)

if flag in s[0]:

return 'No flag for you!', 403

else:

return s

This makes things challenging. The obvious inclination here is to make some sort of Server Side Template Injection (SSTI), but there is a robust check on making sure that whatever we are trying to render doesn’t have the flag. In other words, we can easily access the flag variable, but not easily render it.

However, notice the template method that template_route() calls:

def template(s):

while True:

m = re.match(r'.*({{.+?}}).*', s, re.DOTALL)

if not m:

break

key = m.group(1)[2:-2]

if key not in template_keys:

return f'Key {key} not found!', 500

s = s.replace(m.group(1), str(template_keys[key]))

return s, 200

Let’s break this down. the re.match(r'.*({{.+?}}).*', s, re.DOTALL) checks to find an occurence of {{some text here}} within the s string we pass into the template. The s string is whatever data we posted. If we don’t find this occurence, we break out of the loop and return the original posted data without any changes.

However, if it was found, a key variable is created, and it is essentially passed whatever we posted, but with the curly brackets sliced off. In other words, key = some text here, if we posted {{some text here}}.

The next line is crucial to our exploit. At this point, it checks to see if the key variable is in the template_keys dictionary. If it isn’t, it returns whatever the key value currently is, saying that it wasn’t found. We’ll come back to this in a second.

Finally, s is now changed to the value of whatever key we posted.

So to recap the process, let’s say we POST {{title}}, from the dictionary I put up before. An occurence would be found. The key variable would then be set to title. The if statement would not be true, so s would become the value for title, which is my website. On the next iteration of the loop,no match would be found, and s would be returned. Finally, my website is compared to whatever the flag is (the flag of course is not in it), and it is rendered.

What could go wrong here? It all lies in the second if statement in the template method - it displays a potential key without any filters. After some playing around, the proper data to post to get the flag is {{{{flag}}}}.

When this string is eventually passed to the template method, a match would be found. However, with the way the regex is formatted, it actually finds the match in the innermost part of the string. In other words, the match is found like this: {{{{flag}}}}, and m is a matching object that is ONLY {{flag}}. When we slice off the curly brackets and do the check, it passes, because flag is in the dictionary.

s is then replaced with the actual flag. This is the cool part. We know all flags for this CTF are in the form tjctf{}. When we do s.replace(), we are only replacing the m.group(1) portion of the posted data with the value. To show it more clearly, the bold data is what is being replaced: {{{{flag}}}}.

This means that on the next iteration, s is now {{tjctf{UNKNOWN FLAG}}}. A match is found here, and the key variable is now set to tjctf{UNKNOWN FLAG} However, the actual flag is NOT a key in the dictionary - only the word flag was. The if statement then fails, and we get that nifty error message of the key not being found, which actually displays the flag:

This was by far my favorite challenge of the bunch.

MUSIC CHECKOUT

This was the last one I did.

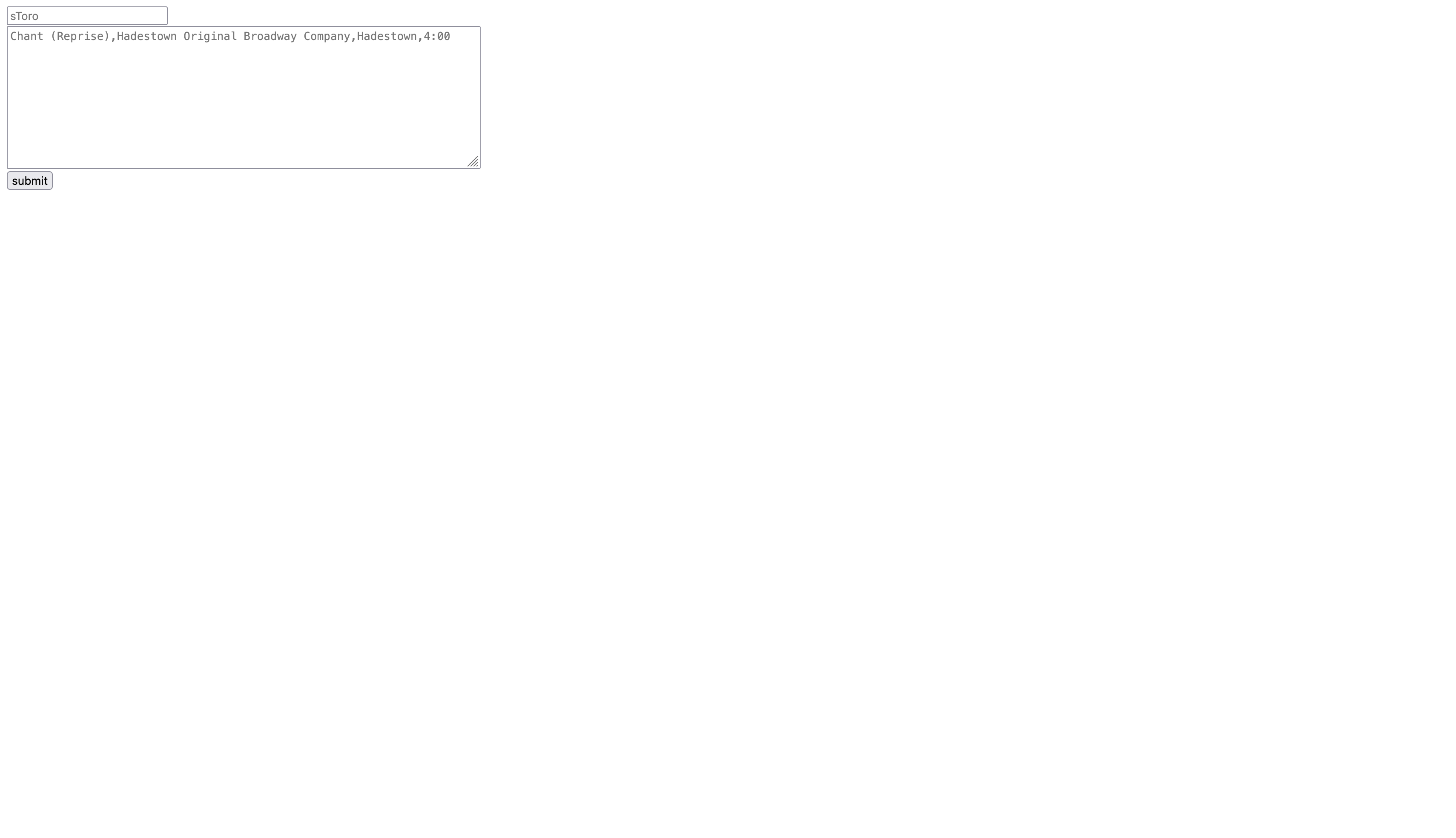

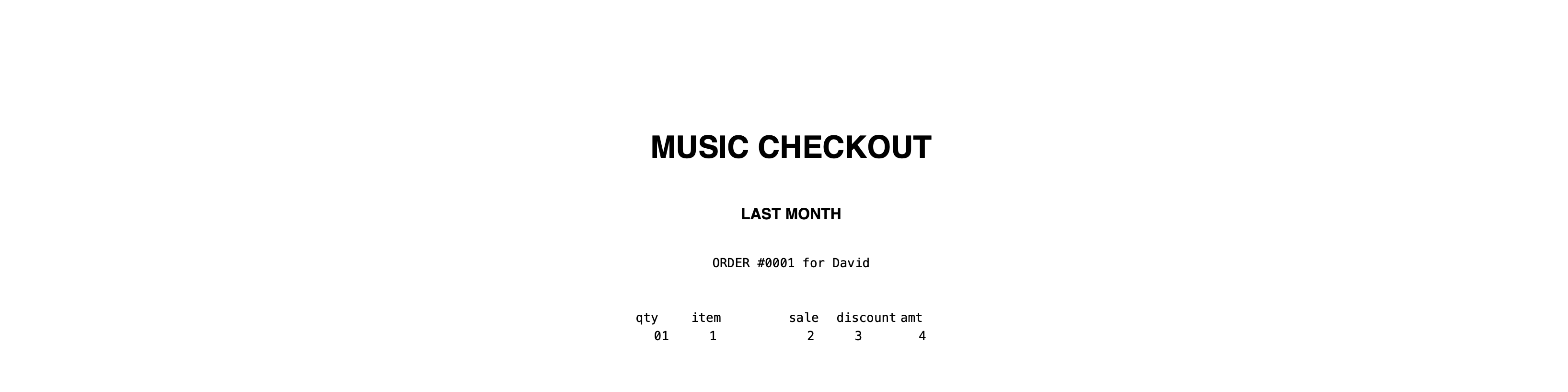

You can submit a username in the small box, and some data that is parsed in the larger box. Upon hitting submit, you get taken to this page:

With the last challenge involving templates, I immediately thought of SSTI. The source code protects from any SSTI via jinja2, as this is a flask app:

def post_playlist():

try:

username = request.form["username"]

text = request.form["text"]

if len(text) > 10_000:

return "Too much!", 406

if "{{" in text or "}}" in text:

return "Nice try!", 406

text = [line.split(",") for line in text.splitlines()]

text = [line[:4] + ["?"] * (4 - min(len(line), 4)) for line in text]

filled = render_template("playlist.html", username=username, songs=text)

this_id = str(uuid.uuid4())

with open(f"templates/uploads/{this_id}.html", "w") as f:

f.write(filled)

return render_template("created_playlist.html", uuid_val=this_id), 200

except Exception as e:

print(e)

return "Internal server error", 500

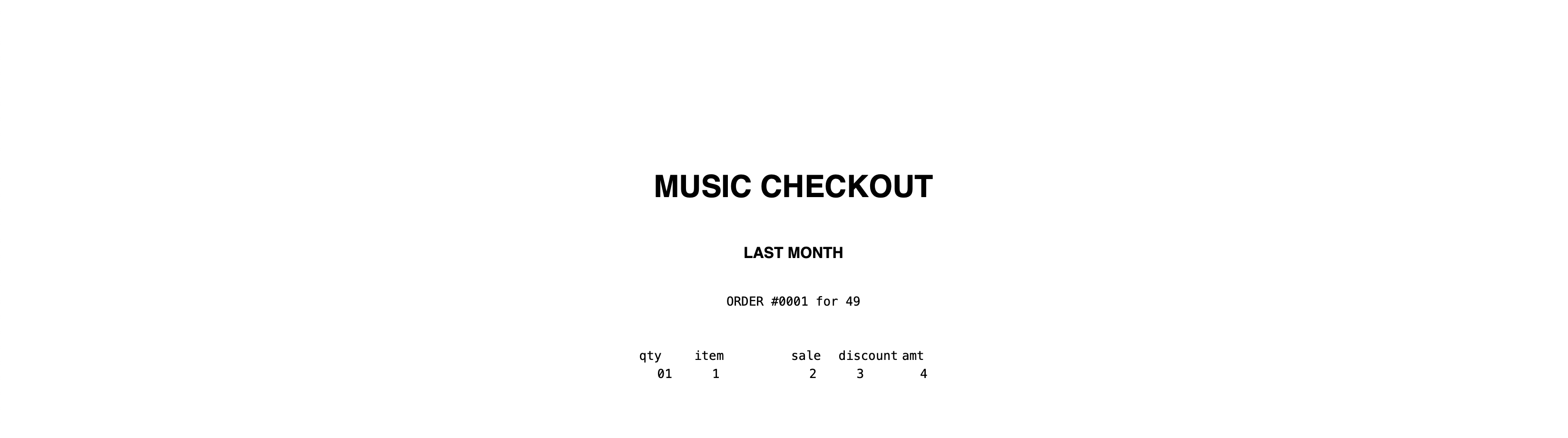

However, as you can see in the above code, it is only checking to see if we put curly brackets in the text field. In other words, the username field is completely unsanitized. I tried POSTing the common payload to test for SSTI {{7*7}} in the username field, and sure enough:

You can see that the order is for 49 instead of {{7*7}} , meaning that the server executed the code within our template. With the power of template engines, we can actually open and modify files through these injections. By checking the source files the CTF provides us with, we can see that there is a flag.txt file in the server.

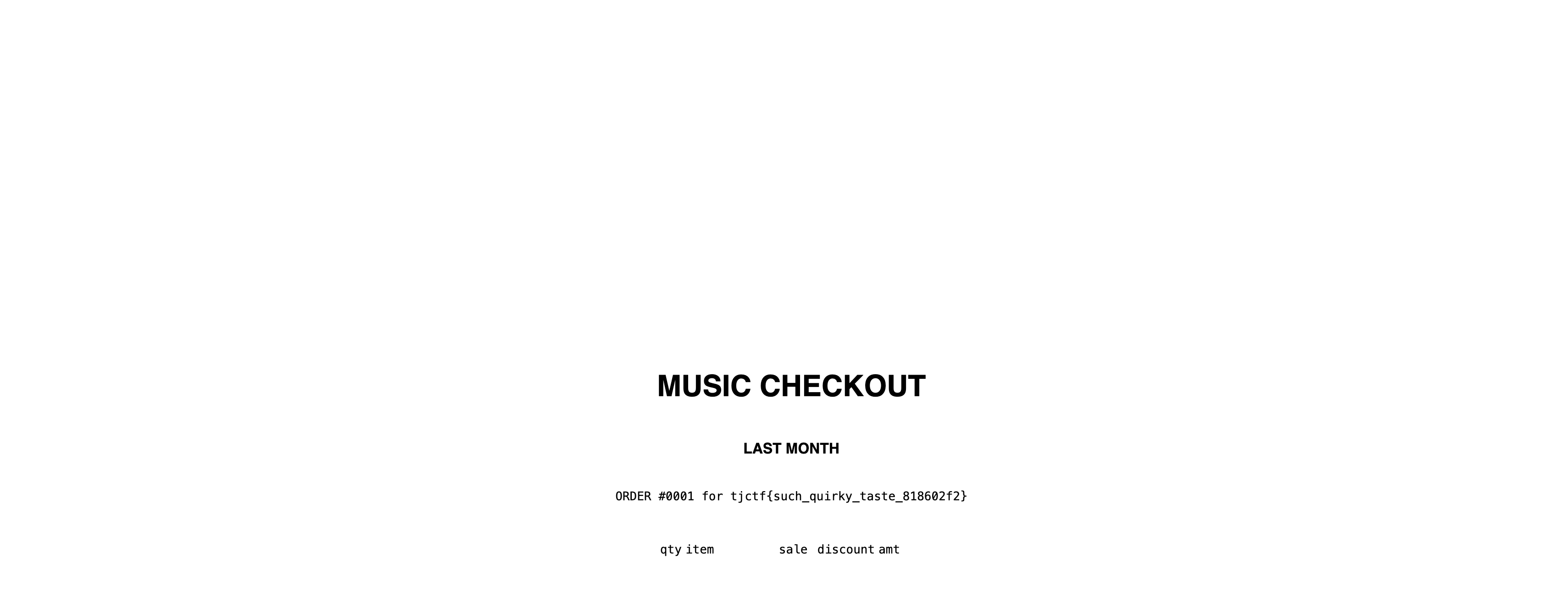

From here, we simply need to craft a payload that opens this file, and we can get the flag. My jinja2 knowledge is somewhat limited, so I used the help of this handy cheatsheet of sorts HackTricks SSTI Payloads to form the payload we needed:

{{ request.__class__._load_form_data.__globals__.__builtins__.open("flag.txt").read() }}

When we submit this to the username field, we get the flag:

These challenges were not so bad. I really liked templater, and this was overall good practice for SSRF and SSTI vulnerabilites. Next week, I will continue with web as my focus, but I’m going to take a crack at some rev and pwn.